Undoing Secrets and Loss: Reading Family Narrative and Reclaiming a Name

In 1906 at age four, my grandmother lost her mother to a cause of death unknown because it was unrecorded and unspoken. About seventy years later, my father mentioned over a weeknight meal that my grandmother also had two older sisters. This was the first I had heard of not one, but three women lost to our family. Death had taken a little girl’s mother, and marriage to practicing Catholics had taken her sisters at a time and place where Protestants marrying Catholics was unbendingly verboten. Within about 10 years of girlhood, my grandmother’s three core influences of family, culture, and women’s ways of learning and knowing permanently were gone. A step-mother entered her life, a person my grandfather once said had treated my grandmother worse than a kicked dog.

These are family narratives, and while little is known, what has been retained and spoken aloud shapes my understanding of my grandmother’s behavior, beliefs and choices — for example, her insistence that her own children remain close, that my cousin always remember me on my birthday (she remembers not my birthday, but that Grandma told her to remember it), and that food can become scarce and working hard earns one the right to eat.

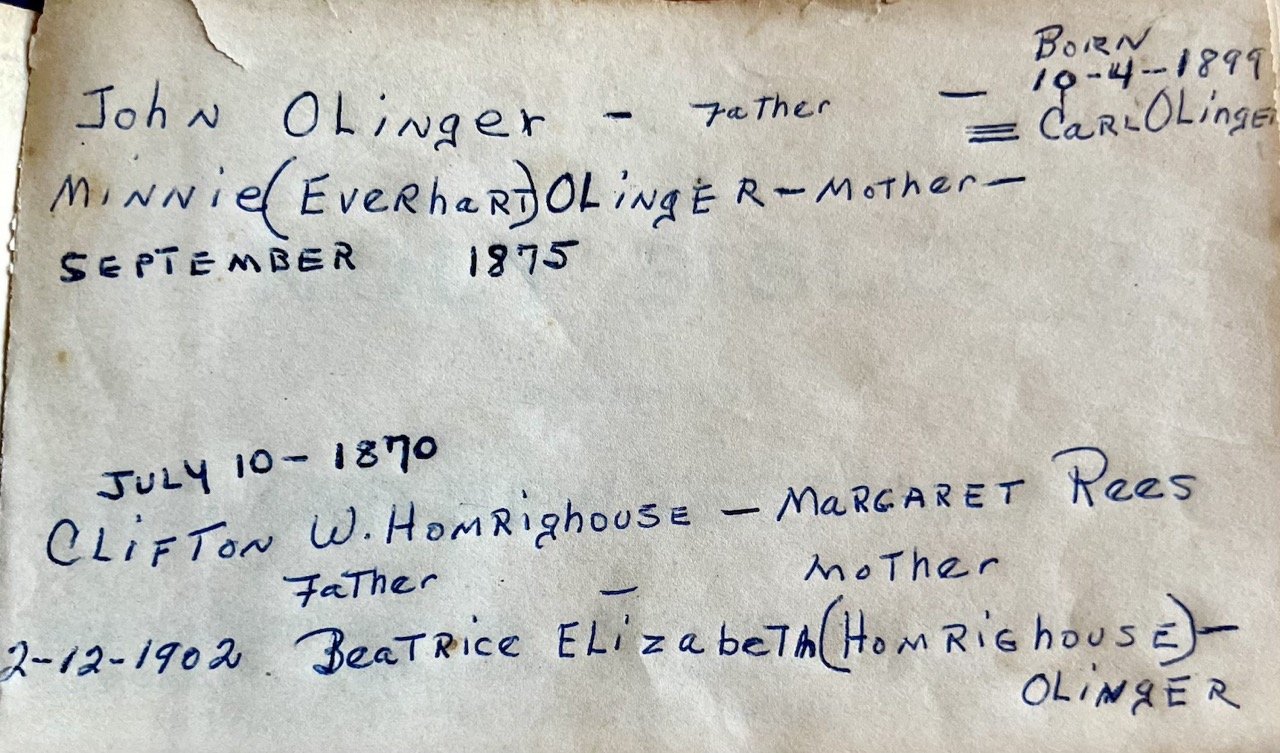

What I have written here is almost all of what I know. Records, including public records, seem scarce, except for this: my grandmother recorded her mother’s name in a family Bible (see image below). Margaret Rées. Two census records show she also went by Maggie, and, when I say the name aloud, it feels uplifting, lively. Maggie. The syllables bubble up. Maggie dancing and celebrating. She had immigrated from Wales in the late nineteenth century, perhaps alone, but had married a handsome man of some humor and had three healthy daughters and an extended family in her new home. Her youngest daughter, Beatrice Elizabeth, will be an artist and philanthropist with her baking and needlework and a celebrated oil painter later in life. Maggie has cause to laugh and dance.

I am researching her. I have found no death record, no grave, no news announcement, just an absence in the U.S. Census records — no longer a line item for Margaret “Maggie” Homrighouse, née Rées.

In online ancestry platforms, I have corrected the record of who my great-grandmother is, exclaiming as loudly as I can across digital space that the hard, mean woman who abused her remaining step-daughter was not my great-grandmother. History shows that Margaret Rées lived, contributed, and died so young and abruptly that, 120 years later, her family still is trying to know what happened.

I am embracing her and resurrecting her. And professionally adopting her name, Rées. The translation of Rées is fiery, enthusiastic, ardent, aglow. Intuitively that feels like the Maggie of whom I am learning, the great-grandmother who, it seems, has my back as I have her unfolding story at heart.

“Home is where your story begins”

reads the inscription on the memorial and grave marker for Zora Neale Hurston in Fort Pierce, Florida. Alice Walker resurrected Hurston’s story, books, bibliography, and spirit in the mid-1970s, reintroducing us all to Zora Neale as I think of her.

If you’re interested, this article by Alice Walker is a brilliant follow up to this blog post. Finding a World that I Thought Was Lost: Zora Neale Hurston and the People She Looked at Very Hard and Loved Very Much

We resurrect our foremothers. In doing so, we meet a starting point to ourselves. Home is where the story begins, but story is a lifeline that takes us home.

There is more to this story to come. Thank you.